Biographies

magazine-30augOpening remarks

Dr. S.H. Albar

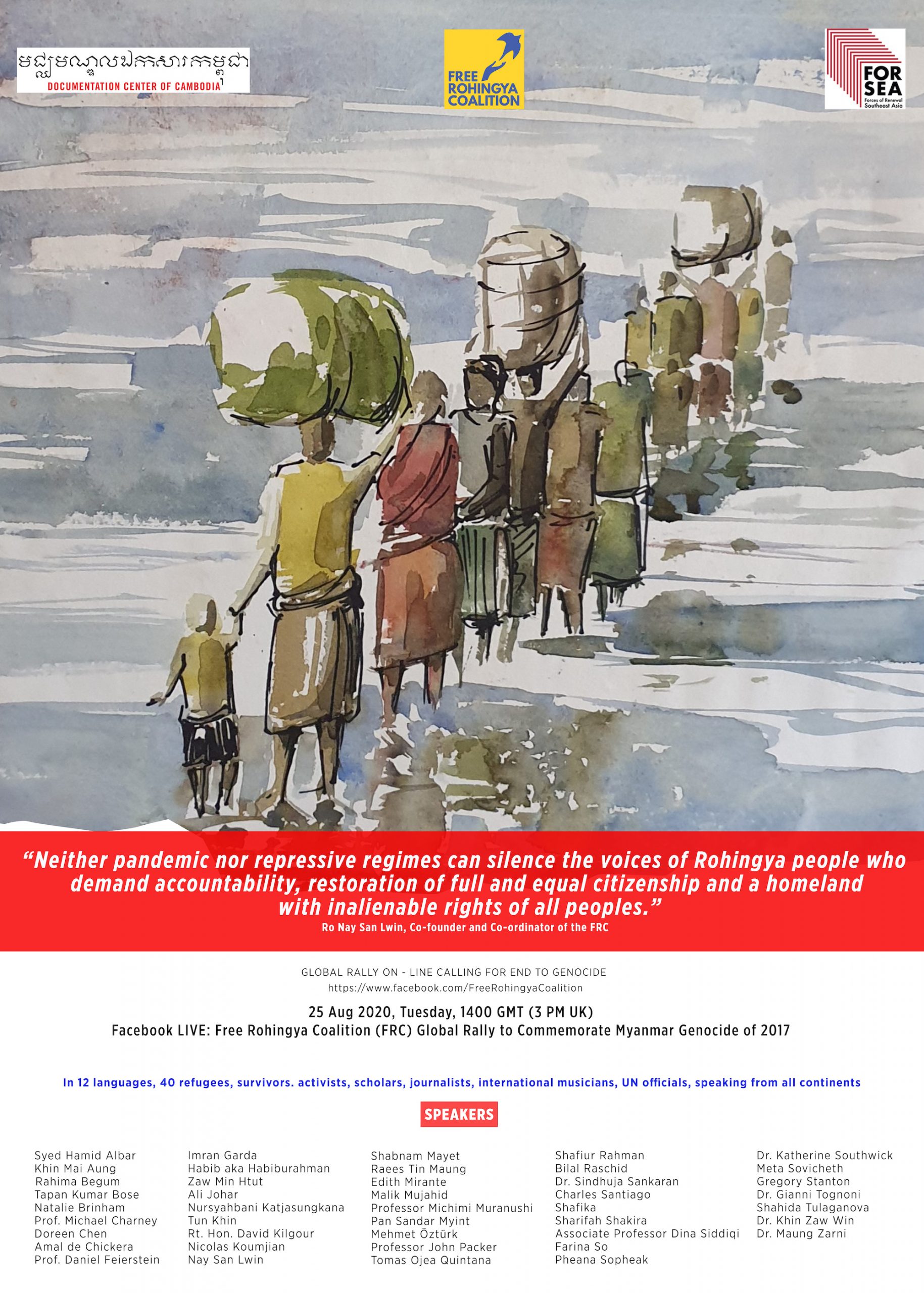

The 3rd Free Rohingya Coalition Genocide Memorial and Rally

Thank you Dr. Zarni for inviting me to participate in this webinar: Free Rohingya Coalition (FRC) global rally to commemorate Myanmar genocide of 27 august 2017. I am extremely honoured to be given this opportunity to make some opening remarks in both english and Malay languages. I’m happy to be together with such distinguished participants from all over the world, in different time zones. Let me congratulate Dr Zarni on his hardwork and resolve in organizing this historical event.

On this commemorative genocide rally we wish to remember, recollect and commit to the ongoing struggle of the Rohingya against the genocide by Myanmar. The date 27th august 2017 was taken as a significant benchmark or the starting point that caused the mass exodus of the Rohingya due to the actions of the security forces of Myanmar which, the international community and the UN have said, tantamount to genocide or classic case of ethnic cleansing. They fled in huge numbers to the closest neighbouring country Bangladesh. It is a day of remembrance and time for sharing the pains and sufferings of the Rohingya mothers, fathers, sons and daughters, friends and relatives who had been tortured, murdered, raped or burned alive in their houses and villages by the security forces and their vigilantes. These heinous crimes were committed mercilessly, just because they were of different religion and ethnicity.

These heinous crimes are still ongoing without accountability of the perpetrators. Justice is still denied to the victims. The Rohingyan longs to return to their beloved homeland and villages as a citizen of the country of their births.

The genocide in Burma didn’t start in the killing fields and villages but it began with the unending rhetoric of hate and intolerance without being abated by the government and political leaders of Myanmar. This gave rise to horrible riots, killings and gross human rights violations. Without a doubt, words of hate and intolerance easily instill prejudices and distrust on people’s emotions and shaped their attitudes and behaviour on others who are different. The government and the political leaders turned a blind eye on all the grotesque crimes committed by the security forces and Buddhist vigilantes.

To remember this date means to share the pains and sufferings of the genocide that occurred. The ordinary Burmese supported the Ma-Ba-Tha, the extremist group of Buddhist monks, government and the security forces in their brutal persecutions and atrocities which had occurred for decades. Since 1948, and in particular in 2012, 2016 and 2017 the same acts were committed. Now its up to the international community and regional powers to pressure Myanmar to stop their atrocities against the Rohingya.

It’s time to reflect why the ethnic cleansing and genocide continued. Myanmar acts with impunity because there was no censure and accountability placed on her. ASEAN, UN, OIC, regional and major powers failed in their obligations towards the Rohingya community in what the un has admitted as the most persecuted people in the world. Long time ago after the holocaust the international community has given an undertaking, “Never Again” they would allow genocide to happen. Yet it remains as words without action. We still failed to prevent the killings and stop the genocide of the Rohingya. Why have these various international, regional multilateral agencies allowed it to continue? Why have they not responded to take action, when the evidence is so clear?

This 3rd anniversary on 25 August of Rohingya is to remind us that the exodus on that date was caused by the genocide of the Rohingya community. This rally is the collective voice of the personalties who believe in humanity and justice to demand for the perpetrators of the crime to be held accountable and stop the genocide. At the same time the refugees in cox bazaar as agreed between Myanmar and Bangladesh demand to return home in a voluntary, safe and dignified manner to their homeland in the northern Rakhine state under the supervision and protection of the UN.

Let me repeat voluminous words, statements, resolutions and calls have been made to the government and leaders of Myanmar demanding them to act but thus far with no effects. What we need now is to force Myanmar to take action. There has been a collective failure of UN, SC, ASEAN and EU and to some degree oic, individual and major regional powers? The international and regional systems have failed the Rohingyan. It will not be wrong to say the genocide against the Rohingyan is their failure.

Myanmar has said it is transiting to democracy as a justification and the problems are complex. But democracy cannot subsists without it being inclusive. The discriminatory laws against the Rohingya is not going to make this happens. Myanmar must be made to acknowledge in democracy human rights and the rule of law are fundamental prerequisites. It is Myanmar’s obligation to strengthen trust in the political institutions and societies they have created, to defend freedom of expression and instilling social justice, (Kofi Annan report). These challenges are fundamentals for sustainable peace, reconciliation and economic development. This rally a significant event organized by Free Rohingya Coalitions (FRC) is most honorable. We hope it would prick the conscience of the international community to act and stop the pains and sufferings of the Rohingyan once and for all. There is no need for any further evidence on the genocide because the evidence are provided by the Rohingya victims and those gathered by the UN bodies and the various independent international NGOS. They speak for themselves.

Let me finally say the solution is both diplomatic and political. ASEAN, UN and OIC and other regional powers, should decisively force Myanmar to adhere, respect international norms and laws. The perpetrators of the crimes be held accountable in order for a sustainable solution to be achievable and genocide stopped. We must strengthen our resolve and efforts. We must learn from history, whether it be the holocaust, Rwanda or Cambodia. This rally is appropriately held to honour the victims of genocide and to register our commitments to the Rohingyan cause.

Thank you, for giving me the opportunity to make the opening remarks.

Statement by Mr. Nicholas Koumjian, Head of the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar, on the Free Rohingya Coalition (FRC) Global Rally to Commemorate Myanmar Genocide of 2017

25 August 2020

I really want to thank all of you that have tuned in to this event because this is a very solemn occasion, of course. We are marking three years since the events that began on the 25th of August 2017 that saw hundreds of thousands of individuals flee their homes in Rakhine state—most of them to go live in refugee camps abroad, some of them displaced from their homes inside Myanmar.

It’s very important to remember those people because what happened to them goes on. Those who cannot go home continue to suffer. Every day that they live outside their homes is another day where their suffering continues. It was in recognition of what was viewed as serious international crimes by the international community that the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar, which I have the privilege to head, was created by the highest UN human rights body, the Human Rights Council.

It was given the mandate not just to investigate these events, but all serious international crimes and violations of human rights committed in the territory of Myanmar since January 1st 2011. The mandate goes on. It covers today. We cover what happens next week, next month, until this mandate is changed by the Human Rights Council. It is a mandate that was endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly. It covers crimes committed against anyone in Myanmar regardless of the ethnicity, the religion, the nationality of the victim, or of the perpetrator.

We’re interested in human beings – anyone who has suffered from a serious international crime. Our hope is to – and our mandate – is to collect evidence of those crimes; to organise and to analyse the evidence in order to determine if there is sufficient proof of the individual responsibility of persons, whether these individuals are criminally responsible for what happened, and then to share that information with national, regional or international courts that may have jurisdiction or be interested in the information.

We have already shared some information with a couple of different courts, including with the International Court of Justice, because we think that proceeding is important. It’s important that the judges get all the evidence, the best evidence, in order for them to reach a well-informed decision in that case.

We depend upon the cooperation of different organisations that have evidence, of agencies, of businesses. And we’ll ultimately depend upon the cooperation of victims and witnesses. We’ll put their security, their privacy, in priority, in first position. Our highest priority would be to ensure the safety and security of witnesses. We look forward to further cooperation from witnesses and from many of you that are tuning in to this event.

I just, again, want to thank you all for your cooperation, for your interest in this. The international criminal justice process is something that is very complex. It normally is very slow. It can take years to accomplish international justice. We understand that while a few years is not much in international criminal justice, for those that are in refugee camps, for those that are forced out of their homes, three years is a very long time. We understand that they want to go home. We’ll do what we can to contribute to eventual justice for those who suffered from these crimes. Thank you.

Shabnam Mayet (English)

Assalamualaikum and good evening everyone

I want to thank the Free Rohingya Coalition for hosting this Genocide Commemoration event.

I was asked to tell you more about Protect the Rohingya this evening. We began in 2012 with a hand full of volunteers and over the years we have organised protests and film screenings. We have briefed various institutions, we have held speaking tours which have brought various Rohingya activists to South Africa and written articles. We have assisted those addressing governments on the issue, and we have been interviewed by the media, students and journalists. We advise various organisations on their projects for the Rohingya and we fundraise for our own.

In 2014 we published a legal report entitled, Hear Our Screams, which was submitted to the UN office for the Prevention of Genocide and in 2015 we published the first e-book about the Rohingya which combined articles, poetry and art, it was edited by myself along with Andrew Day from Canada and Geor Hitzen from the Netherlands.

In 2017 we, are very proud of having, sent an all women legal team to Cox Bazaar, three South African lawyers and a Scottish Journalist. The aim was to take witness statements from refugees who had recently fled Myanmar, these were then made available to international legal teams and were used in international legal matters. The report back was entitled, ‘They Ran for Their Lives’ and it was provided to the UN and the UK Parliament as well.

For our Winter School project in 2018 we collaborated with members of the Rohingya Community Development Campaign to organise a Winter School for one hundred Rohingya young adults. We wanted to give them a university vibe.

Our Oral History project is currently recording the histories of some of the 400 villages which were destroyed during the genocide.

This year marked our seventh annual #Black4Rohingya Campaign which is a social media initiative that asks everyone to wear black and post their messages of solidarity on June 13th. This year we are so excited because we hit 35 000 interactions.

Our belief is that there is no action too small when it comes to working towards the attainment of justice. There is something we can all do, so let us begin by educating ourselves and those around us. Let us support initiatives which empower the Rohingya, let us boycott companies that trade with the Myanmar military conglomerates and let us pressurise our governments to act against the genocide.

Often we speak to people about the Rohingya and their response is, “how can this be happening in 2020?”. And I suppose in a world where information is so freely available to so many and the language of human rights permeates all our conversations, a genocide on our watch seems unthinkable but unfortunately, it is not so.

In December of 2017, three months after witnessing the drone footage of the mass exodus of Rohingya. I had the opportunity to visit the worlds largest refugee camp where 800 000 Rohingya were forced to flee their home of 800 years. Nothing prepares you for the first time you arrive in Cox’s Bazar, there are a hundred thousand horror stories per square kilometre.

When disaster strikes we busy ourselves with the statistics. We count the dead, we count the tortured and the raped, we tally the burnt villages and we calculate the kilometres of stolen land. We quickly forget that the victims of genocide are families, with homes and hopes, with celebrations and love stories and histories.

Despite all they have suffered the Rohingya spirit is unvanquishable. On the 3rd anniversary of the Rohingya Genocide let us remember, that it is not for us to dictate to the oppressed how they should seek their freedom. Our role must be one of support and solidarity. After all, only a historical moment stands between one genocide and the next.

So I hope you will support the campaign and join the movement.

You can find Protect the Rohingya on social media platforms. I wish the rest of the panel all the best and thank you so much once again.

Prof. Gregory Stanton (English)

Genocide is the intentional destruction in whole or in part of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group. Myanmar committed genocide by intentionally destroying a substantial part of the Rohingya ethnic and religious group. The Myanmar Army murdered over ten thousand Rohingya people, destroyed hundreds of Rohingya villages, and raped thousands of Rohingya women. It deliberately created conditions of life intended to destroy the Rohingya group – so that a million Rohingya refugees fled to Bangladesh.

Genocide is a process, not a single event. Myanmar’s genocide against the Rohingya began years before 2017. Rohingya were stripped of citizenship in 1982. They endured genocidal massacres in 2012 and 2016. Genocide Watch declared a Genocide Emergency in 2012.

The U.N., the U.S., the U.K., the New York Times, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International refused to call the crime genocide. They said the intent to destroy the Rohingya wasn’t proven. That is also Myanmar’s defense in the case Gambia brought against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice. Aung San Suu Kyi said the intent was “counterinsurgency” and “ethnic cleansing.” “Ethnic cleansing” isn’t even a crime under any international treaty. It means “forced displacement,” a crime against humanity.

In its erroneous judgments in the Bosnia v Serbia and Croatia v Serbia cases, the International Court of Justice held that if destruction of part of a group is not the only intent – if “ethnic cleansing” is also an intent – then the crime cannot be genocide. Genocide must be the “only intent.” But the Genocide Convention doesn’t say that. It is a false concept of intent introduced by William Schabas, Antonio Cassese, Joan Donaghue and other misleading “legal scholars.” It treats the intent to commit genocide as mutually exclusive from the intent to forcibly displace a people. In fact, both crimes often go together.

Because the International Court of Justice often follows its own precedents, even though it is not required to do so, the case Gambia brought against Myanmar in the ICJ may fail. The ICJ could find that destruction of the Rohingya was not the “only intent” of the Myanmar government. The ICJ must find a way to distinguish around its erroneous interpretations of the Genocide Convention in the Bosnia and Croatia cases.

The International Criminal Court has no jurisdiction over the genocide Myanmar committed on its territory because Myanmar is not a state-party to the Rome Statute of the ICC.

Countries that have universal jurisdiction for crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity could arrest and try the perpetrators of the Rohingya genocide if they come to their countries. That includes most of Western Europe, the U.S., Australia, Argentina, and Senegal.

But even if the ICJ decides that Myanmar has committed genocide, it will not solve the problems of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, Malaysia, and other countries.

The rich nations of the world, who stood by and did nothing while Myanmar committed genocide, must generously contribute the money necessary to support Rohingya refugees. Marc Zuckerberg and Facebook should give billions, for publishing incitements to genocide against the Rohingya.

Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, the U.S., U.K., France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and other nations, the U.N. Human Rights Council, and the U.N. General Assembly must demand that Myanmar resettle its Rohingya people as full citizens of Myanmar, with effective U.N. and ASEAN protection.

Raiss Tinmaung (English & French)

My name is Raiss, I and my family are from Akyab, from Zolda Khana, Nazir fara, Amla fara, etc. all of which do not exist anymore as they have been burned to the ground, bulldozed, and wiped out from the world map. Living in Canada, I am only left to do my small part to bring awareness of the plight of my people, through the Rohingya Human Rights Network and through Free Rohingya Coalition.

For the last 3 years the Rohingya Human Rights Network chapters in cities and provinces across Canada organized rallies, public events, petitions, closed-door meetings, and media engagements to lobby the Canadian government to act in the face of genocide of the Rohingya. Although we saw small fruits of our efforts, such as the declaration of genocide by both houses of Parliament, revocation of citizenship of Aung San Suu Kyi, erection of Rohingya exhibits at 3 mainstream museums in the country, and the provision of aid to the refugee camps, we still have a lot to see, in terms of concrete actions taken in areas of accountability, impunity, targeted economic sanctions, international arms embargo, and etc.

Pour les amis Canadiens qui sont ici, et aussi les autres francophonea qui vont écouter cette émission, je voudrais faire nous rappeler, que notre travail est loin d’etre finis. On a toujours un pays qui continue ses actions d’atrocités contre ses peuples, il continue sa campagne de nettoyage contre les autres éthnies, y compris les Rakhines, les Kachins, les Karens, les Shans et les Chins, apres avoir implémenter, avec succès, un plan du génocide contre les Rohingyas. Si les Canadiens sont vraiment serieux d’etre un pays qui protège les valuers de droits de la personne, il faut que nous prennons, des actions qui montre ses valeurs. Il faut rejoindre le Gambia dans l’action aux cour de la justice internationale, il faut qu’on utilise notre pouvoir dans la scène internationale, pour arrêter l’argent qui subventionne le gouvernement birman, l’argent qui vient de la Chine, le Singapore, le Japon, l’Israel. Il faut faire tous ce qu’il faut pour couper les vois d’armement, qui soutinnent l’armée birmanne. Et finalement, il ne faut pas oublier que dans ce moment de crise financière mondiale, ce serait les camps de réfugiées qui vont être impacter le maximum. Il ne faut pas oublier, les déjà obliées.

Bhai behn doston, Allah tun dua gori ze Allah arar mon ur bhitore qaum ur khidmat, quam ur mohobbat, ar quam ur himayat gori ballai hamesha qubool gorok… Ajjiya sirf 3 bossor no, bohot bossor hoi giyye… Arar qaum ur mustaqbil banai ballai, taleem tarbiyat hasil gori ballai, school banai ballai, hospital banai ballai, arar muashera qaim gori ballai, yan arar bekkunor zimmadari, aar zimmadari. Lihaza Allah tun dua gori ze Allah ay zimmadari pura gori ballai ara bekkun ure qubool gorok. Amen.

Professor John Packer (English & French)

Thank you to the organisers for this wonderful event of which I am honoured and privileged to contribute. Per your request Dr Zarni, I will make my remarks partly in English and partly in French.

I wish to express my appreciation especially to non-Rohingya who recognise the grave injustices that have long befallen the Rohingya and who are acting through your words and personal behaviour to call out the genocide, to call upon others also to do so, and to seek change. These efforts are now needed as much as ever. With 85% of all Rohingya having been forced to flee their homeland and live dispersed around the world, the risk collectively for the Rohingya people is greater than ever. They need our solidarity, our material assistance, and above all they need the repair of their situation – to return home as soon as possible.

I will make three points.

First, the Rohingya situation is not just another example of failed “Never Again”. The Rohingya are us and we are the Rohingya. The situation is a result of man’s inhumanity to man and our failure to stop it. But they are also our hope – an example of resilience and of future possibilities. We share not only vulnerabilities – there but for the grace of God go I – but we also share dreams of good life. The situation of the Rohingya manifest the pain and diminishment of us all. So, I Am Rohingya. Our failure to see this – to feel this – is to deny the universal character of our nature, of our humanity.

Second, the situation of the Rohingya – wherever they are, in Arakan/Rakhine, in the sub-region – is a practical challenge for us all … of whether we will ever live together peacefully and prosperously. This is an issue of global import – of international peace and security. We have an interest in this, to engage and see it redressed, to restore dignity for the Rohingyas, to promote reconciliation, and to contribute to sustainable peace, security and development in Arakan/Rakhine, the neighbourhood, the region and beyond.

Troisièmement, la soif de justice est un désir naturel des individus et des communautés. Elle est innée dans la condition humaine et l’esprit humain. La justice est impérative. Mais la justice sans paix et sans un ensemble de vie durable – surtout et maintenant pour les Rohingyas eux-mêmes – risque de rendre la justice vide. Vous ne pouvez pas boire la justice. Je souligne cela parce qu’il sera très bientôt nécessaire de concentrer nos efforts sur la recherche de solutions. Cela nécessite – inévitablement – un dialogue, notamment avec ceux dont nous voulons voir le comportement changer – à devenir mieux. Leur conduite doit passer de faire du mal à faire le bien. Ce n’est qu’avec eux que les conditions seront réunies pour les Rohingyas dans leur pays d’origine – sûrs, libres dans la dignité et dans la poursuite de leurs pleines aspirations… individuellement et en tant que peuple.

In sum, I wish today as we mark the ongoing Rohingya Genocide that we recognise the Rohingya in a spirit of human solidarity, that we also recognise our shared interests, and finally that, as we pursue justice, we also pursue real solutions that will sooner than later allow the Rohingya to return home and pursue their lives in full dignity and freedom.

Amal de Chickera (English)

Dear friends,

Vannakam, and Ayubowan as we say in my native Sri Lanka. These Tamil and Sinhala greetings carry a particular poignance as we stand in solidarity with our Rohingya sisters and brothers today. By saying ‘vannakam’, I acknowledge and respect the divine within you. By saying ‘ayubowan’, I wish you a long and meaningful life.

These two words encapsulate some of the most fundamental principles which underpin our human rights – dignity, equality, respect, the sanctity of life – ideas that have been trampled and spat upon by the Burmese state and its agents. But just as some who say ‘Mingalarbar’ – the Burmese greeting of prosperity and blessings – found within themselves, the ugliness and inhumanity of genocidaires; so too, have some who say Vannakam and Ayubowan. I am a child of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict. My coming of age story was shaped by the contours of violence, inhumanity and disregard for life. I have screamed with impotence as I witnessed powerful people literally getting away with murder. These same people rewrote histories, a revisionism that paints them as heroes and their victims as villains; that portrays human rights defenders as traitors, and war criminals as patriots. A childhood friend of mine marks his 40th birthday in prison today, a political detainee.

I say this, not to compare – for what you have gone through, and still do, is incomparable. But to say, my solidarity comes from a place of empathy. To say that I harbour the same piercing frustrations, as I watch powerful people dismantle our worlds; even as other powerful people look away, or at best, pay lip-service to vague notions of justice. To say that I too marvel at the moral dissonance of those who claim to represent the best of their traditions and faiths, while so callously tearing them to shreds.

In the lead up to today, I found my thoughts coming back to the words of Rohingya poet Mayyu Ali:

From the day we escaped the genocide,

We count on days.

We count on months.

We count on years.

What we count, always passes away

What we’ve been seeking, has not arrived yet

These words, capture – as only a poets’ can – the sense of isolation, hopelessness and betrayal felt by a community; who having endured a genocide, must now rely on others for protection and the pursuit of justice.

Today we remember the horrors of the 25th of August 2017. But today, we must not forget previous horrors, of 2012, 1991, 1978, and countless others, that irreversibly changed histories – of countries, communities, families and individuals.

The days, months and years counted in Mayyu Ali’s poem, stretch back over decades. Even when Myanmar was a pariah on the global stage, at the height of the military junta, the world seemed to value Rohingya lives ‘less’. It is difficult to think of another context where refugees would be forcibly repatriated en masse, to an authoritarian state that was openly persecuting them. With the Rohingya, this happened twice.

As Myanmar opened up, the value of Rohingya life continued to be ‘less’; their persecution, an inconvenient truth to be sacrificed at the altar of modernisation and democratisation.

If Myanmar’s genocide was possible because to the rest of the world, the value of Rohingya life was less; justice, accountability and security for the Rohingya today feels far away, for the same reason.

Through the horror of genocide, the insecurity of displacement and exile, and the tediousness of having to always show gratitude to their ‘hosts’; Rohingya leaders have retained their dignity, perspective, generosity and humour. They still have faith in the international community and still are able to give others the benefit of the doubt. Those of us who are not Rohingya, must not let them down again.

What we have been seeking, has not arrived yet.

Let us change this, in solidarity, with courage, together.

Vannakam, Ayubowan, Thank you

Hon. David Kilgour (English)

Today is Rohingya Genocide Remembrance Day. Since the intensification of Myanmar’s violence against the Rohingya in August 2017, more than 700,000 Rohingya refugees have fled to Bangladesh; up to 43,000 have been killed; as many as 81,000 women and girls have been impregnated by rape; and more than 360 Rohingya villages have been fully or partially burned to the ground.

It is not only Myanmar’s military that bears responsibility for these atrocities, but also civilian branches of the government under control of Aung San Suu Kyi for enabling them. The state of Myanmar has been made to suffer few consequences.

The Rohingya have been subjected to almost all the forms of treatment listed in the UN Genocide Convention: 1) killing; 2) serious bodily and mental harm; 3) infliction of conditions calculated to bring about their physical destruction as a group (tens of thousands of Rohingya have been confined in “internally displaced persons” camps in Myanmar, where they have been deprived of food, water, and medical care) ; and 4) imposition of measures intended to prevent births (for example, Myanmar’s “Race and Religion Protection Laws” of 2015, which impose restrictions on Rohingya marriages and births).

Under international law, states are obligated not only to prosecute genocide after it has occurred, but also to prevent genocide as it is in process. According to the International Court of Justice, “a State’s obligation to prevent, and the corresponding duty to act, arise at the instant that the State learns of, or should normally have learned of, the existence of a serious risk that genocide will be committed.”

Canada should as the first country to recognize officially the violence perpetrated against the Rohingya as genocide and act commensurately by:

- using all political and economic means to pressure Myanmar to comply with international law in its treatment of the Rohingya, including through imposition of sanctions on all military and civilian authorities responsible for violations;

- re-evaluating all Canadian assistance to and investment in Myanmar, to confirm that individuals and institutions implicated in genocide are not receiving any downstream benefits;

- doing our share to ensure that the humanitarian relief effort for Rohingya refugees is fully funded; and

- supporting efforts to hold the Myanmar state and individuals responsible for genocide accountable.

For the past ten months, the global response to the Rohingya crisis has been in the judicial arena after Gambia – acting at the request of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation – filed a genocide case in front of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Gambia accuses Myanmar of violating the U.N. 1948 Genocide Convention, a human rights treaty to which Canada is also a party, along with 151 other countries.

Last December, Canada and the Netherlands expressed their intention to “jointly explore all options to support and assist the Gambia in these efforts.”

The procedure at the ICJ allows for third states to intervene in the proceedings to make their views known to the court. Canada should not be content to merely watch from the sidelines. It should now avail itself of its right to intervene at the World Court. By making a formal intervention, it can play a central role in bringing justice to the Rohingyas.

The next phase of the ICJ proceedings is due to unfold over the next few years.

Canada, in keeping with its proactive policy, needs to send an important signal of universal solidarity with the Rohingyas. It is also an opportunity for Canada to advance its feminist foreign policy.

In its intervention, Canada could be unique by examining the concept of genocide through a gendered lens. It could address crucial, gendered features of the crime, given the evidence of widespread sexual violence against Rohingya women. It would also complement the Canadian government’s gender-responsive humanitarian approach to the Rohingya crisis. [source: international.gc.ca “Canada’s Strategy to Respond to the Rohingya Crisis in Myanmar and Bangladesh” 2018-05-23]

This case is not just of interest to the Muslim world. Genocide is a matter of concern to the international community as a whole. A coalition of Muslim and Western states has an important symbolic value. It would also help gather worldwide support to ensure compliance with any measures of reparation that might be ordered in the ICJ’s final judgement.

村主道美 Professor Muranushi Michimi (Japanese)

3年前の今日、ミャンマー軍はラカイン州北部でロヒンギャに対する大きな軍事行動を開始し、略奪、放火、強姦、殺人を繰り返し、少なくとも1万人には上るとみられる死者と、荒廃した村々を後にして、70万人のイスラム教徒ロヒンギャが、隣国のバングラデシュに逃れました。こうして新しく膨れ上がった100万人の難民キャンプに加えて、ラカイン州にはなお、強制収容所や、村から出ることを許されない多くのロヒンギャがいます。Three years ago today, the Myanmar army launched a major military campaign against the Rohingya in northern Rakhine State, plundering, arsoning, raping, and murdering, leaving at least 10,000 dead and devastated villages. 700,000 Muslim Rohingya fled to neighboring Bangladesh. In addition to the newly expanded refugee camp of one million people, Rakhine State still has many concentration camps and many Rohingyas who are not allowed to leave the village.

現在、日本人は、このバングラデシュのキャンプの人々の物的な不足のみに目が行き、問題の本質を、いつものことながら、見失いかけています。問題の本質は、ひとつの民族集団を破壊しようとする試みが長期にわたり行われてきており、それがこの国の民主化と外国企業進出の波の中で、隠されていることです。2017年以後、日本政府は、ミャンマーの人権侵害を認める言動は一切慎み、Aung San Suu Kyiと軍の両方をより強く支えてきました。軍がラカイン州での軍事行動を開始する少し前には、その国軍司令官は日本を訪問し、日本政府から歓迎を受けています。国連からは、事態が人道に対する罪であり、Genocideであるという報告書が出ても、それを否定するミャンマー側の独立調査委員会を、日本は積極的に支持しました。Today, the Japanese are, as always, losing sight of the essence of the problem, focusing solely on the physical shortages of the people in this Bangladesh camp. The essence of the problem is that there have been long-standing attempts to destroy one ethnic group, which are hidden in the democratization of this country and the expansion of foreign companies. Since 2017, the Government of Japan has refrained from acting to recognize Myanmar’s human rights abuses, and has strongly supported both Aung San Suu Kyi and the military. Shortly before the army’s military operations in Rakhine State, its army commander visited Japan and was welcomed by the Government of Japan. Even though the United Nations reported that the situation was a crime against humanity and was Genocide, Japan actively supported the Myanmar independent investigation committee, which denies it.

国際司法裁判所にてミャンマーをGenocideの実施者であるとして訴える裁判が開始すると、在ミャンマーの日本大使は、ミャンマーがGenocideを行ったとは思わない、という異例の発言をも記者の前で行いました。そして何より、ミャンマーの意向に沿って、日本は「ロヒンギャ」という言葉を用いず、ミャンマーの政府と軍を力づけてきました。When the International Court of Justice started a lawsuit accusing Myanmar of being an implementer of Genocide, the Japanese ambassador to Myanmar also made an unusual statement in front of the reporter that he did not think that Myanmar did Genocide. .. Above all, in line with Myanmar’s intentions, Japan has been emphasizing the government and army of Myanmar without using the word “Rohingya”.

日本のmediaもまた、「日本は本件で独自の立場をとっている」「ミャンマーでは中国と競争している」「日本は微妙なかじ取りを迫られている」などと、日本政府と同一の立場ではないにせよ、政府に理解ある論説が存在します。日本は、WWIIの後、人道に対する罪の責任を問われました。現在日本は、ユダヤ人やロマ人に対してナチスドイツが取った迫害と同種の行為を、比較的隠れて、比較的ゆっくりと進める国家を、事実上、弁護し、強く支える方針を打ち出しています。Japanese media also have accommodating opinions, if not the same position as the Japanese government, saying that “Japan takes its own position in this case,” “Competing with China in Myanmar,” “Japan is under delicate steering.” Japan was accused of crimes against humanity after WWII. Japan now has a policy of virtually defending and strongly supporting a nation that is relatively hidden and relatively slow in conducting acts of the same kind as Nazi Germany’s persecution against Jews and Romans. .

外国人なら、日本人の人権意識は戦後どこが進歩したのか、疑問視すべきです。日本人なら、森友、加計学園と、国内のありふれた、小さい問題に注目してきた日本社会が、何を見てこなかったかにそろそろ気づくべきです。海外の人々との連帯に関心のある日本人なら、100万人のキャンプにどう薬や食料を送るか、という問題より遥かに身近に、それほどの人々を暴力的に追い出した勢力の、最大の支持者のひとつが、自分達の日本であり、自分達はそれを犯罪とは考えていないということに気付くべきです。If you are a foreigner, you should question where Japanese people’s awareness of human rights has improved after the war. If you are Japanese, you should soon realize what Moritomo, Kake Gakuen, and Japanese society, which have been focusing on common and small problems in Japan, have not seen. The Japanese, who are interested in solidarity with foreigners, are far more familiar than the problem of how to send medicines and food to the camps of 1 million people, and the biggest force of the forces that expelled those people violently. It should be realized that one of the supporters is their Japan and they do not consider it a crime.

そしてこのようなわが国が、日米安保を語るときは、わが国はアメリカと価値観を同じくする、と騙り、国連安保理常任理事国入りの希望を捨てずに、国連をわが国は尊重する、という立場を騙り続けること、そしてロヒンギャの生存に関わる、日本の重要な外交の決定が、国民は無論のこと、国会で政治家に問題にされることもないまま、平凡な外務官僚達によって行われていることに、改めて驚くべきです。And when Japan talks about Japan-U.S. security, it is fooled by the fact that Japan shares the same values as the United States, and Japan will respect the United Nations without abandoning its hope of becoming a permanent member of the Security Council. Japan’s important diplomatic decisions regarding the continued deception of the Rohingya and the survival of the Rohingya are made by ordinary foreign bureaucrats, without the public’s questioning and without being questioned by politicians in the Diet. It’s amazing again.

Dr. Katherine Southwick (English)

Since 2014, I have written articles and advocated about the Rohingya – with FRC and others – in different places. As a scholar of atrocity prevention and rule of law, as a student and advocate for whom it was drilled into my consciousness that we must not allow something like the Holocaust or the Rwandan genocide to happen again, I felt a professional and moral responsibility to say or do something about the situation of the Rohingya and the then “slow- burning genocide” that I could see the world was choosing again to ignore.

International Responsibility

This was a situation where the international community had far more tools than it had twenty years ago – in terms of international law, UN mandates, diplomatic training, and knowledge – to see this coming.

And now, we the international community, which includes the ASEAN community, must use this day to ask ourselves what went wrong and why. What do we really have to lose in admitting the facts, in living by our principles of state and corporate responsibility, and working with all concerned to find – urgently – a lasting solution?

The Black Lives Matter movement and the pandemic have reawakened global consciousness of our interdependence and shared humanity. As U.S. Vice Presidential Candidate Kamala Harris said last week: “None of us are free… until all of us are free.” Therefore, for our lives to matter, wherever we are in the world, Rohingya lives must matter.

Looking Ahead

Many of the things we should have done to prevent atrocities and genocide are the same things we must do looking forward: We must support justice, peace, and equal rights for the Rohingya and other ethnic minorities in Myanmar.

What Rohingya and other activists have accomplished in the last several years in terms of international awareness and response reflects in some ways a successful global movement. You have a diverse range of supporters around the world. You have former UN officials leading efforts to seek justice.

I believe that your most important supporters are the ones from and inside Myanmar, for they are the ones who are working from the inside, from the ground up, to bring about a better Myanmar, one that guarantees equal rights and dignity for all who live there. Under such a system, Rohingya can truly find safety and a future in Myanmar.

This, unfortunately, is typically a long process.

After the Holocaust of World War II – during which millions of Jews were murdered – Germany went through a decades-long process of constitutional and political reform, de-Nazification, and judicial accountability for atrocity crimes. German Jews were given back citizenship, but most did not return. By then, many survivors had rebuilt their lives and communities in other places.

While we must be careful with historical analogies, Germany’s example suggests that for Myanmar to become a place that is safe for Rohingya, and that recognizes their equal rights as citizens of Myanmar, it will require a significant shift in political leadership and constitutional and political reform. These processes usually do not happen in a year or five years.

But if safe return and equal rights is what you want – because it is no less than what you deserve – then those are reforms that we all must support, and ally with the groups and organizations that are doing this work – inside Myanmar.

In the Interim: End Subhuman Conditions of Displacement

In the interim, we must not forget that the situation in the camps in Bangladesh and elsewhere is not acceptable.

This past Saturday, Rohingya activist, Hafzar Tameesuddin, said in her online remarks:

“When people are stripped away from their human dignity, and when people are living a life with uncertainty about what will happen next tomorrow, it is a kind of dying. It is not living. . . . Every single day, lining up to get some food in the refugee camps, begging, and not having any proper psycho-social support for the trauma they have been through, not having any future for the youth, it’s devastating.”

Hafzar speaks the truth. The current humanitarian approach is costly – risking “donor fatigue” – and does not stop the slow destruction of your community.

The international community must invest in solutions where Rohingya refugees can be self- sustaining, fulfilling their potential, and giving back to the communities in which they live, which they can certainly do.

In supporting political reform, your health, education, livelihoods, your identity, and your culture, we must never stop demanding any less than what your humanity – or our humanity – requires. Thank you.

Shafika (Rohingya) Translated into English

I have been living in the camps for 27 years. There are many difficulties in the camps. Despite the difficulties, it is true, we can sleep in peace. There is no fear of being attacked, slaughtered or shot. In our small huts in Bangladesh, we can at least sleep and so we are grateful.

For decades we have had no rations. In the last 3 – 4 years, we have been getting rations. Yet there are problems there. We have to queue and there is much pushing and shoving and it is difficult for women. Water is far from our homes. Drawing water also involves queueing. Even going to the toilet involves this kind of indignity.

As I said we live in small homes. We sit around in the heat. There is no open space. There is no space to catch some fresh air. Another issue are all the clinics that are here. Small ailments are treated with paracetamol but anything serious, then we have no hope. And many have died because of a lack of treatment. Most can’t afford outside medical care. And even if you have some money, you will get stopped at the check post and we can’t access the big hospitals. This is a source of pain for us.

Another serious problem that we face is that our kids will never have any standing. We are grateful for the schools and madrasahs but the children can only study up to Class 2 or 3. If they could study for higher classes, perhaps there would be a future for them. Perhaps they could do something with their lives. But they have no future. Without education there is no future.

If we were in Burma, our kids could have studied to class 10 and got some kind of future. But that is not possible here and this gives us real worries.

We are innocent and yet all these things have been done to us. The world has witnessed all our oppression and all the slaughter that we faced. And yet there is no justice. We tell the people of the world, we need justice. We need to be able to go back to Myanmar. We need to end this life of being a refugee. And that is our earnest hope.

Shafiur Rahman (English)

Thank you for inviting me to speak. I have decided to speak the words of a Rohingya refugee i have known for three years. She comes from the village of Tula Toli where a massacre unfolded on 30 August 2017. Her 16 month old daughter was killed in the attack. The child was snatched from her bosom and thrown alive onto a fire. Altogether, she lost 6 family members in the massacre

The events of three years ago are not over for this young woman and perhaps it will never be, but it has created a resolve in her that is remarkable. Her name is Hasina. These are her words.

They made the women stand in waist-high water for hours. I was there for 9 hours. My baby was in my arms throughout these hours. I saw the killings throughout these hours. Gun shots, killing with knives. I could see the three holes they dug. They were putting bodies in there. I saw the red helicopter drop containers. They brought the containers the three holes, poured in oil and then set the bodies alight. Throughout this time also, they took groups of 5 or 6 women away. I don’t know where. My turn came at 5pm in the evening. They took us to a house next to our own and on the way they grabbed my baby and threw her into the fire. I tried to jump after her but they struck me and my sister in law. We were taken to my neighbours house. Inside they hit us when we resisted rape and made us unconscious. They set the house on fire. My sister in law and I regained consciousness moments before the burning ceiling came down. I often think that if we had been taken to my own home, none of us would have survived. It was built differently. We escaped without any clothes on. We crossed the river and we to had to hide in the fields. Three days later my husband found me after seeing our pictures on Facebook after we found someone in Bolibazar who helped us.

My husband has changed. He is educated and he had a job in Myanmar. He knows English and Burmese. In the camp, he has nothing to do. His face has changed. He thinks all the time about his parents and his daughter and his relatives who were all killed. When I gave birth again in Bangladesh, I lost one twin – during childbirth in my shelter. I have a disabled child.

I tell my husband that we have gone through a lot of hardships. We survived all the killing. So we are going to be alright in the camps. There are many difficulties but we will be alright. I tell him that all the bad things are finished and that in front of us are better days. We had land and cattle in Burma. So when justice is finally achieved, we will go back. I am sure I will see Burma again if god wills. I have hope. I will not end my days here. I will go back and see my village again.

Meta Sovichetch (Khmer)

ប្រទេសមីយ៉ាន់ម៉ានិងប្រទេសកម្ពុជាមានអ្វីៗជាច្រើនដែលស្រដៀងគ្នា។ យើងកើតចេញមកពីក្រុម

មនុស្សតែមួយគឺមន-ខ្មែរ មានអាហារនិងសម្លៀកបំពាក់ដែលស្រដៀងគ្នា និងបញ្ហាសំខាន់ដែលមានដូចជា ការរំលោភសិទ្ធិមនុស្ស ការកាប់សម្លាប់ទ្រង់ទ្រាយធំ និងជាពិសេសអំពីប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍។

ហេតុអ្វីយើងត្រូវយកចិត្តទុកដាក់ចំពោះអ្វីដែលកំពុងតែកើតឡើងទៅលើជនជាតិរ៉ូហ៊ីងយ៉ា? ចម្លើយគឺថានេះគឺជាទំនួលខុសត្រូវខាងសីលធម៌របស់យើងក្នុងការចែករំលែកបទពិសោធន៍និងដើម្បីការពារអំពើឃោឃៅពីការកើតឡើងម្ដងទៀត។

អំពើប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍របស់ខ្មែរក្រហមដែលបានកើតឡើងនៅក្នុងប្រទេសកម្ពុជាចន្លោះឆ្នាំ ១៩៧៥-១៩៧៩ បានសម្លាប់ជីវិតមនុស្សជិត ២ លាននាក់។ មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលឯកសារកម្ពុជា (DC-Cam) គឺជាវិទ្យាស្ថានស្រាវជ្រាវមួយដែលប្ដេជ្ញាប្រមូលចងក្រងឯកសារស្តីពីភាពសាហាវឃោរឃៅនិងអប់រំយុវជនជំនាន់ក្រោយអំពីប្រវត្តិសាស្រ្តនិងផលប៉ះពាល់ក្នុងរយៈពេលវែងនៃអំពើហិង្សា។ មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលឯកសារកម្ពុជាបានផ្តល់ឯកសារជាង៥០០,០០០ ទំព័រដល់អង្គជំនុំជម្រះវិសាមញ្ញក្នុងតុលាការកម្ពុជាតាមការស្នើសុំដើម្បីនាំជនដែលទទួលខុសត្រូវខ្ពស់បំផុតទៅតុលាការ ហើយយើងសន្យាថានឹងបញ្ចូលប្រវត្តិសាស្ត្រខ្មែរក្រហមទៅក្នុងកម្មវិធីអប់រំថ្នាក់ជាតិ។ មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលឯកសារកម្ពុជាបានសហការជាមួយក្រសួងអប់រំយុវជននិងកីឡានៃប្រទេសកម្ពុជា ដើម្បីបណ្តុះបណ្តាលគ្រូប្រវត្តិសាស្រ្ត ភូមិសាស្ត្រ អក្សរសាស្ត្រខ្មែរ និងសីលធម៌ពលរដ្ឋ និងចូលរួមជាមួយសិស្សនិងយុវជនក្នុងសកម្មភាពផ្សេងៗនៃការអប់រំអំពីអំពើប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ក្នុងលក្ខណៈផ្លូវការនិងក្រៅផ្លូវការ។

នៅក្នុងឆ្នាំ ២០១៤ មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលឯកសារកម្ពុជាបានធ្វើទស្សនកិច្ចទៅប្រទេសមីយ៉ាន់ម៉ាដើម្បីស្វែងយល់អំពីការរំលោភសិទ្ធិមនុស្ស។ យើងក៏បានផ្តល់ការបណ្តុះបណ្តាលផ្នែកចងក្រងឯកសារដល់ដៃគូរបស់បណ្តាញឯកសារសិទ្ធិមនុស្ស ឬអេនឌី-បឺម៉ា (ND-Burma) ។ អេនឌី-បឺម៉ា គឺជាអង្គការសំខាន់មួយដែលធ្វើការចងក្រងឯកសារស្ដីពីការរំលោភបំពានសិទ្ធិមនុស្សនៅក្នុងប្រទេស។ វគ្គបណ្តុះបណ្តាលនេះផ្តោតសំខាន់ទៅលើវិធីសាស្រ្តប្រមូលឯកសារសិទ្ធិមនុស្សដែលអាចប្រើប្រាស់សម្រាប់គោលបំណងផ្សេងៗដូចជាការស្រាវជ្រាវ ការអប់រំ និងប្រើប្រាស់នៅក្នុងតុលាការ។

បន្ទាប់ពីការបណ្តុះបណ្តាលបានបញ្ចប់អ្នកចូលរួមចំនួន ២ នាក់គឺ Nang Htoi Rawng និង Chit Min Lay ត្រូវបានជ្រើសរើសដោយផ្អែកទៅលើចំណង់ចំណូលចិត្ត ការលះបង់ និងលក្ខណៈសម្បត្តិរបស់ពួកគាត់ដើម្បីធ្វើកម្មសិក្សារយៈពេលខ្លីនៅមជ្ឈមណ្ឌលឯកសារកម្ពុជា។ Nang Htoi Rawng បម្រើការងារនៅសមាគមស្ត្រីកាឈិននិង Chit Min Lay គឺជាអតីតអ្នកទោសនយោបាយហើយបច្ចុប្បន្នកំពុងបម្រើការងារនៅអិនឌី – ភូមា។ ជាផ្នែកមួយនៃការបណ្តុះបណ្តាលនៅនឹងកន្លែង ពួកគាត់ត្រូវបាននាំទៅទស្សនានៅតាមកន្លែងប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ដូចជាសារមន្ទីរប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ទួលស្លែង (ដែលគេស្គាល់ថា ស-២១) និងវាលពិឃាតជើងឯក ជួបជាមួយអ្នករស់រានមានជីវិត និងជួបជាមួយសហគមន៍ផ្សេងៗ និងទស្សនាតំបន់វប្បធម៌ផ្សេងៗ។ យើងក៏បានបង្កើតកម្មវិធីបណ្តុះបណ្តាល សិក្ខាសាលា ឬការបង្រៀនផ្សេងទៀតសម្រាប់ប្រជាជនមកពីប្រទេសភូមាដោយមានមាន Wai Nu អតីតអ្នកទោសនយោបាយនិងជាស្ថាបនិកនៃបណ្តាញសន្តិភាពស្ត្រីដើម្បីចូលរួមជាមួយយើងផងដែរ។

យើងនឹងបន្តបើកវគ្គបណ្តុះបណ្តាលឬសិក្ខាសាលាស្រដៀងគ្នានេះដើម្បីជួយមិត្តរបស់យើងក្នុងការជំរុញយុត្តិធម៌និងការផ្សះផ្សាគ្នា។

នៅក្នុងប្រទេសកម្ពុជាយើងក៏បានធ្វើការអប់រំអំពើប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍និងលើកកម្ពស់ការយល់ដឹងអំពីអំពើប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ដោយបានធ្វើការជាមួយគ្រូជាង ៣០០០ នាក់ សាលារៀនជាច្រើន សិស្សរាប់ពាន់នាក់ និងអ្នករស់រានមានជីវិតនិងសហគមន៍របស់ពួកគាត់នៅទូទាំងប្រទេស។ហើយគឺពិតជាមាន សារៈសំខាន់ណាស់ដែលយើងធ្វើឪ្យវគ្គសិក្សាប្រវត្តិសាស្រ្តមានលក្ខណៈជាកាតព្វកិច្ចសម្រាប់និស្សិតនិងយុវជនជំនាន់ក្រោយដើម្បីឪ្យពួកគេស្វែងយល់អំពីអតីតកាលនិងស្វែងរកការពិត។ តាមរយៈនេះ ពួកគេនឹងអភិវឌ្ឍការយល់ចិត្តជាមួយនឹងជនរងគ្រោះតាមរយៈការពិតដែលបានលាតត្រដាង ការផ្សះផ្សាក៏លេចចេញជារូបរាង ចំណែកឯការការពារក៏កើតមានឡើង។

យើងនឹងចែករំលែកបទពិសោធន៍របស់យើងជាមួយបណ្ដាប្រទេសដទៃទៀតនៅអាស៊ីអាគ្នេយ៍និងលើកកម្ពស់ការយល់ដឹងអំពីអំពើប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ជាពិសេសក្នុងចំណោមយុវជនអាស៊ានជំនាន់ក្រោយដើម្បីឱ្យពួកគេអាចបញ្ចេញទស្សនៈរបស់ខ្លួននិងចូលរួមចំណែកក្នុងការការពារអំពើឃោរឃៅពីការកើតឡើង។

បច្ចុប្បន្ននេះយើងកំពុងបង្កើតបណ្តាញយុវជននិងអ្នកស្រាវជ្រាវនៅក្នុងអាស៊ានដើម្បីចងក្រងជាឯកសារអំពីទស្សនៈរបស់ពួកគេទាក់ទងនឹងភាពសាហាវឃោរឃៅក្នុងប្រទេសរបស់ខ្លួននិងអំពើឃោរឃៅរបស់ខ្មែរក្រហមក៏ដូចជាយុទ្ធសាស្រ្តនិងសេចក្ដីណែនាំស្ដីពីវិធីដើម្បីការពារការកើតឡើងនៃអំពើឃោឃៅ។ យើងជឿជាក់ថាការចងក្រងឯកសារស្រាវជ្រាវនិងការអប់រំយុវជនជំនាន់ក្រោយនិងអ្នកពាក់ព័ន្ធអាចជាទម្រង់មួយនៃការការពារអំពើប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍។

Farina So (English)

Myanmar and Cambodia have many things in common, ranging from history, culture to political conflict, just to name a few.

-Historical lens: Mon-Khmer–ethnic groups found Burma, Thailand and Cambodia

-Cultural perspective: Food and dress (certain dishes and dresses are similar)

-Political conflict: Gross human rights violations, mass atrocities and genocide

Why we care about Rohingya? it is our moral responsibility to share our experience with and prevent the atrocities from recurrence.

The Khmer Rouge genocide that took place in Cambodia between 1975-1979 claimed almost 2 million lives. Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), a research institute dedicated to documenting the atrocity and educating younger generation about the history and long-term impacts of the violence. DC-Cam provided over half a million pages of documents to the ECCC upon requests in order to bring those most responsible to justice and we assured that the KR history is integrated in the national curriculum. In collaboration with the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport, DC-Cam has trained teachers of history, geography, Khmer literature and civic morality in the curriculum and engaged students and youth in genocide education’s various activities in formal and informal settings.

Back in 2014, DC-Cam team, including DC-Cam’s director, my colleagues and I, conducted a trip to Myanmar to learn about human rights violations and offer documentation training to Network of Human Rights Documentation (ND-Burma)’s partners, a leading membership organization dedicating to documenting human rights abuse in the country. Follow up trips occurred in subsequent years. The training was focused on how to collect human rights documents that can be used for multifaceted purposes, ranging from research, education to court case.

Following the training, two participants, Nang Htoi Rawng and Chit Min Lay, were selected based on their passion, dedication, and qualifications to do a short-term internship at DC-Cam for phase 1. Nang Htoi Rawng is with Kachin Women’s Associations and Chit Min Lay is a former political prisoner and works for ND-Burma. As part of the on-site training, they were brought to see genocidal sites—Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and Choeung Ek killing fields, talk to survivors and meet with various communities, and visit various cultural sites. Other training, workshop, or lecture for people from Burma were to follow through and we had Wai Wai Nu, a former political prisoner and founder of Women’s Peace Network, to join us as well.

We will continue to do similar training or workshop in order to assist our friends in advancing justice and reconciliation.

Speaking of genocide awareness and education in Cambodia, we have reached out to over 3,000 teachers, hundreds of schools, hundred thousands of students, and hundred thousands of survivors and their communities across the country. It is important that we make the history curriculum compulsory for students and young generation, so they will learn about the past and search for the truth. Through this, their empathy will be developed as truth revealed, reconciliation is to take shape as empathy developed and prevention is be built as they are aware of it.

We will share our experience with other nations of Southeast Asia and raise genocide awareness, especially among younger generation of ASEAN, so that they can express their views and contribute to preventing the atrocity from happening.

Currently, we are building networks of youth and researchers in ASEAN, documenting their views about their own country atrocity relation to KR atrocity and strategies & recommendations of how to prevent it. We believe that documenting, researching and educating younger generation and relevant stakeholders can be a form of genocide prevention.

Natalie Brinham (English)

“There is a very grave importance to a day of remembrance, when those who lost their lives remain uncounted. When their deaths remain unrecorded. When their lives remain unacknowledged by the state that annihilated them. August 25th is a day to ensure that those uncounted and unnamed people are not erased from our collective consciousness. It is a day to reflect on the capacity of one group of human beings to inflict unimaginable brutality and cruelty on another. A day to make sure memories are not erased when the fickle media cycles move on.

But It is also a day to honour the survivors.

“I am not defined by my scars, but by my incredible ability to heal”

These are the words of the of the British Ethiopian poet Lemn Sissay, who had his identity stolen from him by the British State. Three years have passed since a wave of genocidal violence was unleashed on the Rohingya people in their homelands in Rakhine State. The collective wounds and trauma suffered by Rohingya can never be fully healed. But if anything in these past three years, the Rohingya have become defined not by their victimhood, but by their incredible ability to survive, to revive and to rejuvenate as a people. Despite Myanmar’s attempts to destroy them, astoundingly, Rohingyas have strengthened their identity. They have strengthened their voices, and in the midst of all their pain celebrated their unique language, their cultural heritage and practices, their music, their poetry, their crafts.

There is a lot of talk of how victims of genocide and the stateless are dehumanised, pushed into spaces of bare humanity. How they become disenfranchised, voiceless, cast outside the reach of law and politics, made sub-human. But Rohingya are the living proof that these processes can and are resisted. Over the past three years, Rohingya have demanded to be heard in the international corridors of power. And they have been. They have not only spoken by invitation on other people’s platforms. They have built their own platforms from nothing. They have not only spoken the words that are deemed acceptable by powerful people in international spaces. They have spoken in their own voices – no matter how inconvenient, no matter how uncomfortable.

As outsiders, as academics, as NGO workers – actively listening to those voices – is an act of solidarity. When we chose our language, we should choose the language of solidarity because we are more than researchers or staff members – we are also human beings with emotion and compassion. Standing with Rohingya in solidarity means:

· We do not ask them to use words that fit our NGOs donor objectives, or our legal analysis. We listen carefully to inconvenient voices and act on them.

· We do not just use the term “ethnic cleansing”, we use genocide.

· We do not speak of conflict resolution; we speak of protection.

· We do not speak of repatriation without first speaking of justice and restitution.

· We do not call Rohingya stateless, without first calling them Arakanese.

· We do not talk of long-term residency; we talk of homelands.

· We do not speak of pathways to citizenship; we talk of citizenship restoration.

· We do not talk of democratic elections, without first speaking of the excluded and disenfranchised.

· We do not give or take money and resources, without first questioning whether it legitimises or supports criminals and the state entities they have built around them.

· We do not act out of convenience; we act out of conviction.

· We listen, we speak and we act because we hold the unimaginable suffering and strength of Rohingyas in our hearts.

Rohingya genocide did not begin on August 25th 2017. It did not begin weeks, months are even years before – it began decades ago. We watched the slow burning genocide unfold. Instead of acting in solidarity, academics, NGO staff, UN and government officials acted out expediency, pragmatic diplomacy, fundability and so-called objectivity. Even the battle to call genocide genocide and Rohingya Rohingya has been a long struggle. Time now to honour the survivors with our solidarity.”

Pheana Sopheak (Chinese)

缅甸和柬埔寨有很多共同之处,比如历史、文化、政治问题和其它方面。

- 历史透视:蒙-高棉民族创造缅甸,泰国和柬埔寨

- 文化透视:餐饮和服装(有着类似的膳食及礼服)

- 政治问题:大量侵犯人权、大规模暴行和种族灭绝

我们为什么要重视罗兴亚难民危机?答案就是、这是我们的道德责任。我们应该分享自己的经验和防止暴行再次发生。

1975至1979年期间,在柬埔寨所发生的红色高棉种族灭绝事件造成近200万人死亡。柬埔寨文献中心(简称DC-Cam)是一间研究所。该中心决心收集好暴行有关资料以及教育年轻一代了解暴力的历史和长期影响。DC-Cam应要求向柬埔寨法院特别法庭(简称ECCC)提供了50多万页的文件,以便将最负责任的人绳之以法,我们保证将红色高棉时代的历史纳入国家课程。DC-Cam与柬埔寨的教育、青年和体育部合作,在课程中培训历史、地理、高棉文学和公民道德教师,并使学生和青年参与正式和非正式环境中的种族灭绝教育的各种活动。

在2014年,DC-Cam团队,包阔本中心主任、我的同事和我,为了了解侵犯人权的情况,对缅甸进行了一次访问。我们并向人权文献网络(简称ND-Burma) 的合作伙伴提供文件培训。ND-Burma是一个致力于记录该国侵犯人权情况的主要成员组织。我们多次后续旅行发生在几年后。该培训的重点是如何收集可用于从研究、教育到法院案件等多方面目的的人权文件。

当培训结束,两位参加者 -—— Nang Htoi Rawng 和 Chit Min Lay,根据他们的热情、奉献精神和资格,被选中。之后,他们在DC-Cam进行第一阶段的短期实习。Nang Htoi Rawng 在克钦族妇女协会工作。Chit Min Lay 是一位前政治犯,目前为ND-Burma工作。作为现场培训的一部分,他们被带去参观灭绝种族的遗址——吐斯廉屠殺博物館(又称S-21) 和柬埔寨金邊瓊邑克處刑場,与幸存者交谈,会见各社区,并参观各种文化遗址。为缅甸人民举办的其他培训、讲习班或讲座也将继续进行,我们还邀请了一位前政治犯、妇女和平网络创始——Wai Wai Nu,加入我们的行列。

我们将继续举办类似的培训或讲习班,以协助我们的朋友推进正义与和解。

谈到柬埔寨境内的种族灭绝意识和教育,我们已向全国各地3,000多名教师、数百所学校、数十万名学生和数十万幸存者及其社区进行了宣传。重要的是,我们把历史课程作为学生和年轻一代的必修课,这样他们就会了解过去,寻找真理。通过这一点,他们的移情将随着真相的揭示而发展,和解将随着移情的发展而形成,预防也将随着他们意识到这一点而建立起来。

我们将与东南亚其他国家分享我们的经验,提高对种族灭绝的认识,特别是在东盟年轻一代中,以便他们能够表达自己的观点,并为防止暴行的发生作出贡献。

目前,我们正在东盟建立青年和研究人员网络,记录他们对自己国家的暴行与红色高棉暴行的关系的看法,以及如何防止这种暴行的战略和建议。 我们认为,记录、研究和教育年轻一代和相关利益攸关方可以是防止灭绝种族的一种形式。

(终)

Khin Mai Aung (English)

I’m Khin Mai Aung. I’m originally from Myanmar. I’m Buddhist, and I’m Bamar and Rakhine.

After Myanmar’s horrifying purge against the Rohingya in August 2017, I saw a need for Buddhists with roots in Myanmar like me to speak out against these atrocities, and promote a more inclusive and tolerant Myanmar national identity.

So, I began to write opinion pieces speaking out as a Burmese Buddhist, and applying my lens as an American civil rights lawyer to that crisis.

Over the last few years, I met and collaborated with many of today’s amazing speakers, with Rohingya and allies to move toward justice for the Rohingya and other oppressed minorities of Myanmar.

I’ve also met many brave Burmese activists living within Myanmar who challenge its racist religious nationalism in the face of enormous personal risk.

Despite how far as we still need to go to toward justice for the Rohingya and other Myanmar minorities, I want to take a moment to reflect on how far we’ve come.

We’ve made incredible progress at building solidarity between Rohingya and other religious and ethnic minorities of Myanmar.

Progressives among ethnic minorities from Myanmar – Karen, Chin, Rakhine, and others – are now working together to promote a more inclusive Myanmar national identity.

When the International Court of Justice issued a provisional order supporting the Gambia’s genocide case against Myanmar this winter, Burmese citizens in downtown Yangon initiated the Black Shirt Campaign publicly speaking out in support of the Court and toward justice for the Rohingya.

We’ve also made progress at building awareness within the international Buddhist community about the toxic danger of Buddhist nationalism.

We’re coming to terms with how our religion is not immune to corruption, and to perversion as a tool of right wing nationalism.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has created barriers to maintain this progress.

As Malaysia turns away Rohingya refugees, overcrowded refugee camps in Bangladesh and displaced individuals on the Myanmar-Thai border have difficulty social distancing and getting personal protective equipment and sanitation supplies.

The COVID crisis has also exacerbated the vulnerability of religious and ethnic minorities in Myanmar and its displaced communities.

It’s stoked repression of vulnerable populations in Myanmar itself and hampered their access to healthcare and reliable public health information.

Social distancing measures have been disproportionately enforced against religious minorities.

The few Rohingya remaining in the country and other minorities are subjected to arbitrary and harsh enforcement for violating social distancing requirements.

Religious minorities, as well as migrant workers returning from other countries, have been quarantined or jailed under overcrowded and unsafe conditions.

The country has had internet shutdowns in minority areas – like Rakhine and Chin states – that have experienced civil unrest.

In Rakhine, the Burmese military has stepped up its efforts during the pandemic to crack down on Rakhine seeking autonomy – including civilians and politicians.

The military has also put in roadblocks to gain control of areas in Rakhine, which has made it harder for civilians to get to hospitals.

We need to expose the injustice of how COVID has been leveraged by Myanmar to step up ongoing oppression of ethnic and religious minorities, and how this has not only oppressed those minorities but also hampered their very ability to protect themselves from COVID.

We live in a radically different world than we did three years ago in September 2017.

We have reason for hope – like the growing solidarity between different ethnic minorities of Myanmar – and new challenges – like the global pandemic which we face together.

But I find strength and comfort in the networks that we have built and the work that we’re doing together to move toward a safe, healthy, just world for us all.

Nursyahbani Katjasungkana (Bahasa Indonesian)

Assalamualaikum warahmatullahi wabarakatuh.

Pertama-tama saya sampaikan terimakasih atas kesempatan dan kehormatan untuk berbicara dalam forum webinar yang juga dihadiri oleh para pembicara yang sangat mumpuni dan ahli dalam bidangnya masing-masing. Penghargaan kepada Maung Zarni dan team yang telah bekerja tanpa lelah untuk terus mengingatkan kepada dunia tentang genosida terhadap Rohingya.

Hari ini kita menundukkan kepala bagi mereka yang menjadi korban baik yang telah tiada maupun yang masih hidup di pengungsian atapun yang masih berada di Myanmar. Pada tanggal 21 Agustus yang lalu kita memperingati Hari Korban terrorisme. Bagi saya terrorisme tidak terbatas pada pengertian yang selama ini ada yakni yang terkait dengan keyakinan agama, tapi juga terror karena masih berlangsungnya impunity.

Anda semua pasti mengetahui peristiwa kejahatan serius dan genocide yang terjadi di Myanmar terhadap etnik group Rohingya, dan yang tetap berlangsung sampai saat ini dan pelakunya masih menikmati impunity atas perlindungan negara. Menurut PM Bangladesh, Hashina di muka siding PBB, setidaknya terdapat 1,1 juta pengungsi Rohingya di Bangladesh saat ini. Kondisi hidup mereka akibat kekejaman yang dialami sangat mengenaskan melampaui imaginasi kita sebagai manusia. Lebih dari 650 ribu orang lagi yang masih berada di Myanmar dengan stigmatisasi, pemenjaraan, persekusi dan genosida yang berlanjut. Belum lagi mereka yang tinggal di kamp-kamp pengungsian di Malaysia, Indonesia , Philipina dan di tempat-tempat lainnya yang mungkin tak banyak mendapat perhatian dunia namun mengalami kehidupan mengenaskan. Anak-anak dan perempuan, sebagaimana terjadi pada kondisi perang dan atau dalam peristiwa pelanggaran-pelanggaran hak asasi manusia berat lainnya adalah kelompok yang paling parah mengalami pelanggaran itu, karena tidak saja terkait dengan kondisi hidup mereka tapi karena kekerasan seksual yang mereka alami termasuk menjadi korban penculikan, perdagangan perempuan dan penyalalahgunaan seksual dan perkawinan paksa atau perkawinan anak-anak.

Anda juga mengetahui bahwa PBB telah membentuk team pencari fakta untuk membuktikan dugaan adanya pelanggaran serius hak asasi manusia dan genosida tsb di Myanmar. Dalam laporan setebal 444 halaman itu yang presentasikan pada 24 Oktober 2018 dalam sidang Komisi Hak Asasi Manusia PBB, team yang diketuai oleh Bapak Marzuki Darusman dari Indonesia berkesimpulan bahwa telah terjadi kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan dan genosida di Myanmar terutama yang berdampak sangat berat bagi suku Rohingya selain suku-suku lain terutama dari negara bagian Kachin dan Shan, Rakhine.

Sebelumnya pada tanggal 18-22 September 2017, sidang Pengadilan Rakyat Internasional yang diselenggarakan di Kuala Lumpur, dimana saya menjadi salah satu anggota Panel Hakim, juga berkesimpulan bahwa kejahatan perang khususnya yang dialami suku Kachin, kejahatan terhadap Kemanusiaan dan genosida dialami oleh suku Rohingya. Jauh sebelumnya saya juga aktif dalam Asean Parliamentarian Caucus for Myanmar, kelompok anggota parlemen yg mengkampanyekan pembebasan Aung San Suu Kyi. Sangat menyedihkan bahwa saat ini dia menjadi bagian dari rezim di Myanmar.

Sampai saat ini pihak militer dan actor non negara lainnya yang merupakan pelaku kejahatan serius dan genosida tsb menikmati kebijakan impunity yang diberlakukan di negara itu. Tak ada sangsi apapun dari negara maupun dari Lembaga-lembaga PBB yang seharusnya berkewajiban menjaga perdamaian, keamanan dan keberlanjutan pembangunan di dunia ini.

Agak berbeda dengan kasus genocida yang terjadi di Vietnam, dimana para pelakunya telah dibawah ke Pengadilan Internasional meski diselenggarakan di Vietnam sendiri, pelaku Genosida yang terjadi di Myanmar dan juga yang terjadi di Indonesia pada tahun 1965/1966 menikmati sepenuhnya impunity yang menjadi karakteristik sistim politik dan hokum kedua negara ini. Rezim pemerintahannya dengan didukung oleh actor non negara selalu menolak mengakui fakta dan kebenaran yang telah dipresentasikan oleh PBB dan Lembaga internasional lainnya, para peneliti dan pembela hak asasi lainnya. Suara korban tak pernah didengar. Langkah-langkah kearah terjadinya persekusi yang potensial berujung pada genosida tetap terjadi. Bahkan untuk memberikan humanitarian aid pun sangat sukar. Setelah dibisukan selama 50 tahun, para pembela hak asasi manusia dengan dukungan para akademisi dan para seniman khususnya pembuat film Joshua Oppenhimer berhasil membuka mata dunia tentang kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan dan genosida yang terjadi di Indonesia, dengan menyelenggarakan International People’s Tribunal tentang kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan 1965. Meski semula IPT 1965 ini terbatas kepada kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan, namun panel hakim menemukan unsur-unsur genosida dalam pembantaian satu juta orang yang dianggap berafiliasi terhadap Partai Komunis Indonesia. Belajar dari pengalaman ini, betapa panjangnya jalan untuk meraih keadilan, bahkan untuk membuka dunia sekalipun. Budaya pembungkaman, culture of silence, seputar issue genosida, apalagi menyangkut kepentingan ekonomi dan politik negara-negara pendukung rezim,begitu kuat.

Jika negara pelaku genosida tsb dan Lembaga-lembaga Internasional tidak melakukan kewajibannya dalam melakukan langkah untuk menghentikan impunity dan memberikan proteksi kepada Rohingya maka kita masyarakat sipil wajib berkomitmen untuk mengakhiri impunity ini dengan berbagai cara. Tak semua hati manusia mati, beku dan membantu. Saya percaya bahwa suatu saat kelak akan ada suatu masa dimana pelaku kejahatan ini akan diseret ke Pengadilan. Pengalaman saya di Indonesia, setelah diselenggarakannya IPT 1965, banyak orang terutama anak muda yang berminat membaca dan mempelajari genosida ini. Beberapa platform dibuat agar ada diskusi diantara para keluarga korban sekaligus mendokumentasikan penderitaan yang dialami keluarganya. IPT 1965 juga telah mendorong pendokumentasian bukti-bukti, cerita, penggalian kuburan massal serta penerbitan buku, jurnal dan penulisan peristiwa-peristiwa di berbagai tempat dalam bentuk puisi, lagu, poster, lukisan, film dst. Semua itu dilakukan untuk meningkatkan kesadaran dan budaya penghormatan hak asasi manusia meski perlawnan dari para pendukung impunity semakin massif. Saya tahu bahwa pemerintah Indonesia tidak membuat posisi yang jelas tentang Rohingya. Pada tanggal 6 July yang lalu pengungsi Rohingya kembali tiba di Aceh, dan duta Besar Indonesia untuk Myanmar mengulang cerita pemerintah Myanmar dengan mengatakan bahwa orang-orang Rohingya tidak datang dari Negara Bagian Arakan / Rakhine (Myanmar) tetapi dari kamp pengungsi Bangladesh, dan bahwa mereka adalah pemukim pada waktu penjajahan Inggris karena kebanyakan dari mereka tidak dapat berbicara bahasa Myanmar. Saya mohon maaf atas misleading ini.

Karena itu saya mengajak teman-teman di Indonesia dan negara ASEAN lainnya untuk menggunakan segala cara yang mungkin untuk mengakhiri impunity yang masih tyerus dinikmati oleh pelaku, apakah itu di Myanmar, Indonesia atau di tempat-tempat lain dimana korban kejahatan terhadap kemanusiaan dan genosida belum memperoleh keadilan.

Webinar kali ini adalah platform yang baik untuk kemudian dilanjutkan secara berkala terutama untuk melawan lupa dan menghentikan impunity

Kepada saudara-saudara saya Rohingya dimanapun berada, doa, semangat dan dukungan saya untuk anda untuk mengakhiri impunity ini. Kepada saudara-saudara saya bangsa Indonesia, adalah saatnya kita bersama-sama mendesak negara Indonesia untuk ikut mewujudkan perdamaian di Myanmar dan dunia lain sesuai dengan mandate konstitusi kita.

Doreen Chen (English)

Today marks three years since your people experienced a modern genocide that drove out nearly a million of you Rohingya from your homeland.

I have no doubt that many of you are disappointed that as of today, accountability and justice has yet to be achieved for your suffering.

To you, the bloodshed probably feels like only yesterday. And yet you may fear that the lack of concrete justice so far — and your increased isolation with the coronavirus pandemic — means that the international community has forgotten about you.

Now we at the Free Rohingya Coalition can’t speak for the official institutions working on Rohingya accountability. But we have not forgotten about you or the genocide, and we are doing all we can to make sure that those institutions don’t either.

And for what it’s worth, I do believe that accountability is coming. It gives me hope that three independent institutions are right now examining your experience from three perspectives:

- You have the UN mechanism which is focused on understanding what happened and building up evidence in that regard.

- There is the International Court of Justice, which is assessing how much Myanmar, as a nation, can be held accountable for the violence.

- And then there is the International Criminal Court, which is looking into the individual accountability of those it considers most responsible.

But I have to caution you that the road to justice is a long one. It takes a long time to process evidence and put it through all the hoops necessary to establish accountability legally, while following all the proper processes. This is true even in your everyday case, so you can imagine how much it amplifies when we are talking about the experiences of literally millions of people.

Now I don’t say that to depress you but to help you set some realistic expectations of what justice may look like and when you may see it. One of the quotes that I live by was made famous by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And it is that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice” in the end.

At the same time, that doesn’t mean that we should all relax because the march towards justice is inevitable. No, in this sense, one of the other quotes I live by is something that Bobby Kennedy said when reflecting on South Africa’s apartheid regime, and it is this:

“Each time a person stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, they send forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

At the Free Rohingya Coalition, we believe that justice must not only be for but by Rohingya — that each one of you can be the most important agent for change for the lives of your people.

So my call to action is for you to think about what the ripple of hope is that you can send out to sweep down those walls of oppression and resistance. What can you do to spark change?

This is of course completely up to you. But here are three things I have seen that have been effective over the years:

- Memorialise the experience of your people. Remember it, record it, and share it, because eventually — a long way down that road towards justice — the narrative of accountability will be woven together from the strands of your individual stories. And future leaders among you can only build a better society for you by understanding your shared history.

- Stay vigilant, and build up your capacity to monitor and document any future atrocities against you. Because unfortunately, history shows us that genocide and crimes against humanity can be continuing or recurring crimes, so the best way to obtain accountability for them if they do occur is to have concrete evidence of what’s happened.

- Participate more actively in accountability, and amplify diverse voices from within your people to reflect the diversity of your experiences. Assert yourselves and insert yourselves. After all, if the accountability is all about you, it should include you.

If we can support you in the road ahead, please reach out; we are here for you. In any event, we offer you our ongoing solidarity and we hold space for you in our hearts and minds. Thank you.

Edith Mirante (English)

Greetings from the “semiautonomous zone” of Portland, Oregon in the United States to Rohingyas and other viewers.

Thanks to Zarni and Nay San Lwin for organizing this gathering about Rohingya genocide, and to all the participants.

I run an information project about Burma (Myanmar) human rights and environmental issues that I founded in 1986. In 1991, I was on the Bangladesh/Burma border when I met some of the first Rohingya refugees who fled Burmese military oppression in what would become a desperate exodus of 250,000 fleeing to Bangladesh that year and 1992. I took their pictures and wrote the first news story about it.

This was a situation — Rohingya civilians, families fleeing Burma’s military campaigns of genocide — that had happened before, particularly in 1978

and would keep happening. In 2016 and 2017 the smoke of burning Rohingya villages rose for the world to see, but for all the international awareness the genocidal violence was not prevented and even basic criminal accountability is a process that only really began in late 2019.

Genocide is ongoing with conditions including severe restriction of movement for remaining Rohingyas in Burma (Myanmar), particularly the concentration camps in Sittwe (Akyab) and arrests for attempting to travel elsewhere in the country.

In January 2018 I wrote an op ed for the Dhaka Tribune in which I called for Rohingya refugee occupied spaces in Bangladesh to be reimagined as new green, sustainable cities that would benefit Bangladesh as well as the current Rohingya residents.

Despite refugee efforts, these urban spaces instead are still treated as mere “camps” with blue tarp huts on eroded hillsides. Seasonal flooding is a persistent problem, which can and must be fixed, including in the “no man’s land” area which is always especially vulnerable.

Currently over 300 Rohingya refugees, captured from a stranded ship are held by Bangladesh in inhumane captivity on a remote mud flat island, Bhasan Char in the cyclone-swept Bay of Bengal. They must be freed immediately and this dangerous prison island needs to be scrapped once and for all as a concentration camp for refugees.

All countries and organizations must always respect the agency of Rohingyas — no decisions should ever be made without the affected people involved directly. Rohingyas have proved over & over again that they are never passive or voiceless victims. They are people with social and political goals and great capacity for community organizing, creativity and mutual aid.

To repeat what Ali Johar said earlier, “It is not a humanitarian crisis, it is a political crisis between the Rohingya and the Myanmar government.”

Education and internet access need to be consistent and reliable on both sides of the border. And Rohingya’s right to livelihood, fair wages and working conditions must be ensured.

I am also hoping for increasing solidarity and support for Rohingya people from the other ethnic peoples of Arakan, with whom they share much in common.